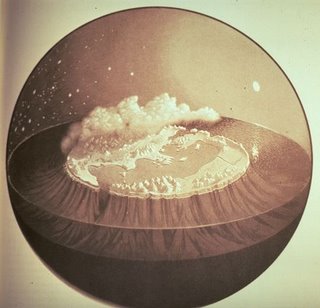

After the flood.

After the events of the flood and the dream of the masked girl the qualities of the Great Hall began to leave a remarkably different impression on me. The long corridors, deep in shadows, the luminous vault of the library in the afternoon, the lunch time walks through the gardens... they all seemed to flatten out, to cease to draw me into that same intoxicated gaze through which I had up until that point observed the various dimensions of this place. As I used to imagine the building as a body, teeming with its corporeal components, the people like the flow of blood in the veins and the walls and rooms the tissue and organs, now when I sat on a clear afternoon on my bench on the terraced footpaths and looked out across the gardens and the Hall and the city, I instead saw something more akin to an ant farm. The glass wall of the library seemed only the small frame in the wooden stand, set to expose the chambers and the tunnels of the colony, to allow the intrepid observer access to the hidden world, where the workers and scouts moved about in their implicit repetitive motions.

I remember not so long ago I would wake up in the morning and instantly, abruptly, a procession of ideas, wishes, vague hopes and goals, would flit about, would rise and turn and shift before my half woken eyes. I would try briefly to trace each to its origin, the secret desire that came before me in abstract terms, in symbols fixed in my memory that related to my interior life in ways that I had yet to untangle. They were not yet distilled into words but still they existed, and something ominous and pressing was behind them. In them I became aware of an approaching dread that I had woken back into my own skin, my own life, that I was doomed today to repeat the doom of yesterday and all that saved me were these impalpable images that hinted at a second life, another field of possibility that lived beside me, running parallel to my own particular stream. And throughout the day these hopes and floating possibilities colored everything before my eyes as much as the sun did, or the little lamps that always hung above my head.

Now each morning I found myself empty, alone, in a new and vacant world, swept clean, as if the dream I just woke from, instead of opening up a portal to my dark, interior world, now only obliterated the self of the previous day, left no shards to trace. I wondered where all I wanted went. I sat at my desk and thought of the last year here in the Hall and all that I had imagined and come to discover, how each year circles are added to my sphere, my knowledge and my intuition grow... but I felt my hopes had halted. I didn't know who to reach out to, I didn't know if there was anyone to reach out towards, or if I had missed something, lost something...

But in losing that undefined thing, I had come to find these words, and these words I must sustain to sustain myself. And I close my eyes and whisper to the girl in my dream, "These are the words of my recollection that I am using to fasten you in my memory, to find and still myself in the center of motion. I cannot clamor and grasp for things that have passed, flail in my sorrow for voices and faces that have faded away. All that has passed is now a vast landscape of impressions, a skyline, a rooftop, a bridge, a mouth... I can only wait in mute patience for some spark to flare like when a match is struck in the dark and I see something of myself in the shadowy eyes in front of me. I had come such a distance from that point, I can hardly remember when I was there. But I can organize my impressions, what lingers, I can see them as songs and I can make houses out of words and places for all of them to populate and they can live with me, in me, changed as they would be, but alive, and I too could live."

And it was at this time, when I was losing my hope for anything beyond these walls, when I was ceasing to remember the dream of the girl, when the majesty and the terror of the Great Hall were diminishing and I began to feel myself wavering like a dry leaf caught in the wind, only tenuously holding on to its branch, that I got my first promotion.